Atriums in Museums

Cass Leach

Architecture is a phenomenological discipline in the sense that the only understanding of architecture is when you move with your body through the space—when you experience the overlapping perspectives. If you turn your head or turn your body you see a different space unfolding, you sense a different texture, you feel a different materiality. That is really the way to experience architecture: you can’t see it in a book properly; you cannot experience the acoustic realm, the realm of materiality, that spatial energy, the changing light. If we allow magazine photos or screen images to replace experience, our ability to perceive architecture will diminish so greatly that it will become impossible to comprehend it.

Steven Holl, Art and Space

This book is not intended as a replacement for actually experiencing the immensity and grandeur of the Gardner's and Harvard Art Museum's atriums. The photos herein will never be able to convey the feeling of moving through these spaces. However, I hope that with my description and analysis of these spaces and photos, we may gain a better understanding of the psychological effects of atriums in museums and how they contribute to the overall theme of the museum, as well as how the art pieces within refract through that theme.

1

Modern atriums developed out of the rectangular open patios around which Roman houses were built. Now, they are frequently the entrance halls of stately buildings. With the advent of modern glass manufacturing, the majority of atriums are entirely enclosed, but still let in natural light as if they were open to the air.

The use of atriums in museums is an expected part of the natural progression of museum architecture. Museums originated as gallery spaces within the houses of the wealthy, often consisting of a hallway with paintings on one side and a wall of windows opposite. This idea of the gallery space continued into the modern era, and was incorporated into the design of many museums, including the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston. The traditional mediums of art in museums, painting and sculpture, require a great deal of light to fully experience. As such, a "concern with natural light was a feature of many modern museums." In order to address these concerns, museum architects such as Alvar Aalto began experimenting with skylights, which are better at diffusing natural light evenly over the room than windows in the walls, generate more wall space for paintings, and can light interior rooms.

While the Gardner was built well before the modern era, its design had to reconcile these same concerns with lighting. In the Gardner museum, the art is mainly arranged gallery-style and lit with windows opposite the art, as in the 'Dutch Room.' However, the center of the original museum consists of a large atrium, with massive glass panels acting as skylights closing the atrium to the air. The light from this atrium illuminates a decent portion of the museum, including John Singer Sargent's El Jaleo.

Atriums, like those at centers of the Isabella Stewart Gardner and Harvard Art Museums, are extremely common in modern museums. They are capable of simultaneously meeting several functions asked of museum architecture. They not only provide light for the viewing of art, but also act as clear landmarks, resting locations for visitors, and bellwethers for the unifying theme of the museum.

2

3

4

Chiefly, atriums provide shelter from the elements. Their glass roofs keep out all weather, maintaining a relatively constant temperature within the atrium, while also letting in as much light as an open courtyard. Additionally, visitors can see out of the roof and into the open sky, providing them with a visual link to nature.

The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum's atrium in particular evokes a connection with nature. The floor of the atrium is entirely covered with a garden which changes composition every few weeks. This garden is full of flowering plants and Greco-Roman statuary, exuding an air of calm and rest. While visitors are not allowed to enter the garden, benches for visitors to rest on ring its outskirts. Within, the garden itself, decorated with a small stone casket and funerary statues, is a metaphorical place of rest for Isabella Gardner's son, Jack.

Atriums in museums are commonly used as places of rest. They often contain bathrooms, information desks, and cafés. The Harvard Art Museum's atrium is minimal, with only half a dozen tables and chairs scattered about. In the corner is Jenny's Café. Harvard students and professors use the atrium for studying, informal meetings, and general leisure.

Museum atriums are not only a place for resting the body, but are also places for resting the mind. A central atrium allows visitors to escape from the surrounding galleries, avoiding visual overstimulation from viewing the art. Museums with wings without central atriums, such as the Museum of

5

Fine Arts in Boston, can often feel like twisting labyrinths of art. By providing a clear landmark, and encouraging a sensible layout of the museum, central atriums allow visitors to engage with the art without constantly trying to determine their location in the museum.

Museums can often be characterized by their overarching theme or genre: a unifying idea or aesthetic which pulls together its individual pieces into a greater whole. To give a particularly blunt example, the Museum of Modern Art in New York City's overarching theme is "modernism." Most themes, however, are more subtle. Luckily, they can often be inferred from the architecture of the museum. Generally, more grandiose the piece of architecture, the easier it is to pinpoint a theme.

There are few rooms more grandiose than an atrium, which tends to be

6

massive, bright, and loud. As such, it is perfect for determining—and setting—the theme of a museum. The older section of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum is the palazzo, so called because it was constructed to resemble a Venetian palace. The faux-marble walls and arches of the atrium, as well as the Greco-Roman sculpture inhabiting its garden, recall in the visitor the mediterranean courtyards of Rome and Venice. These courtyards were common in the public buildings of Rome and later Italy. These public buildings were themselves mimicking the styles and layouts of wealthy homes, which were built around courtyard gardens. Thus, the Gardner's architecture is really calling forth the architecture of the Italian home.

Now the theme of the Gardner is apparent. This museum is a home. Upon further inspecton, this theme resonates throughout the entirety of the museum's collection. A large portion of the art displayed in the Gardner is furniture: fine chairs, tables, easels, and many other things. Renaissance portraits hang from the walls of the Titian room like they depict Gardner's

7

ancestors. The railing for the stairs up from the first floor is recycled from the wrought iron headboard of a bed. There are no wall plaques,indicating the make or title of the pieces. All of this, together, makes the Gardner museum resonate with a feeling of being home—or at the very least being in someone else's home.

Through the employment of this theme, the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum provides a measure of context for the works being displayed within, somewhat addressing Quatremère de Quincy's remarks that the work placed in a museum has been "lifted from its original function, displaced from its birthplace, and rendered foreign to the circumstances that gave it significance" by granting the piece a renewed significance in a new context. This allows the pieces in the Gardner collection to be recombined with other pieces; "Set at a distance from their original uses, past works can be joined by new ones produced specifically for display as works of art."

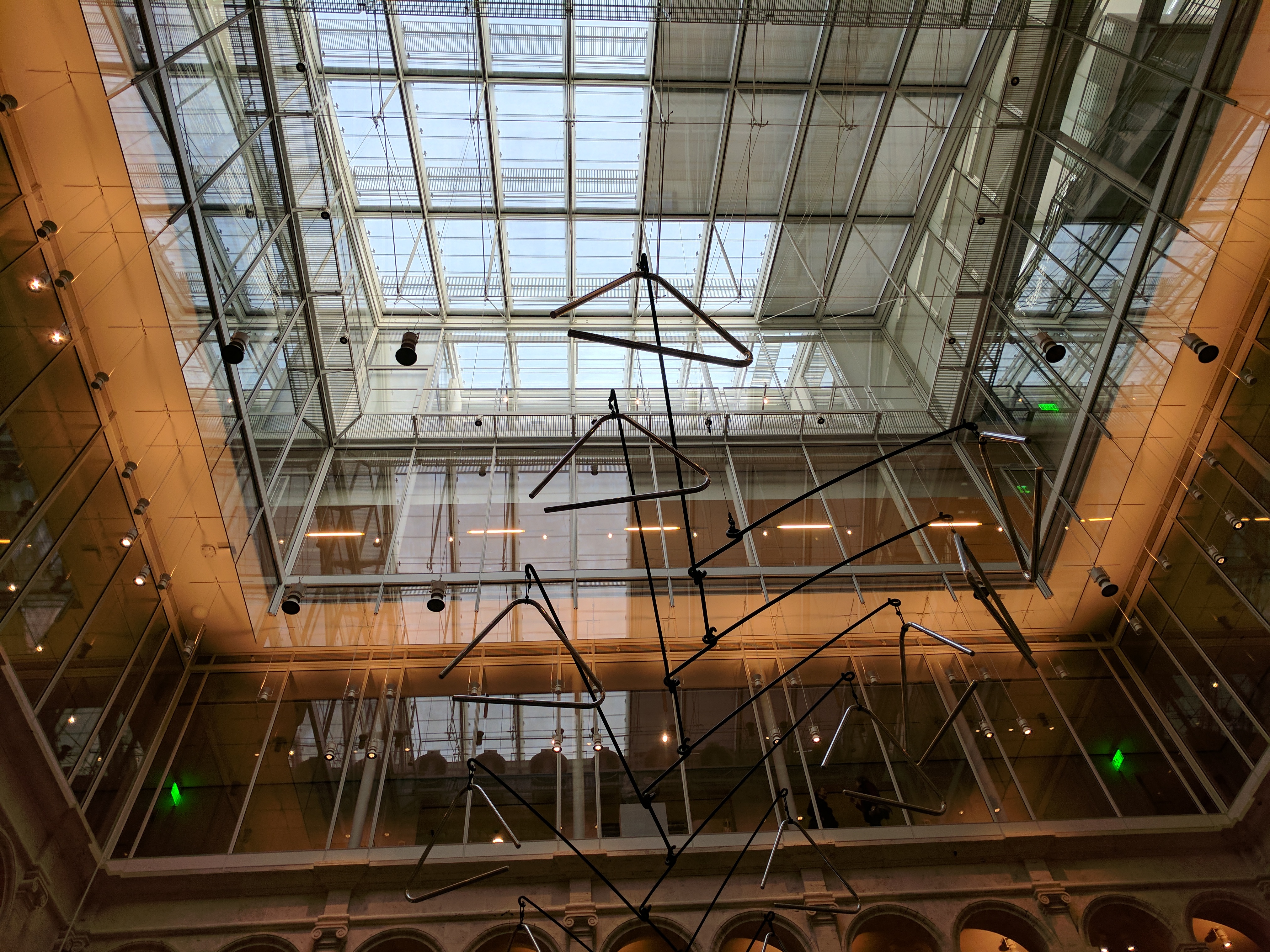

A similar analysis can be made of the Harvard Art Museum's atrium. With its soaring stone columns topped on the third floor with marble statuary, it recalls ancient Greco-Roman temples—civic places of worship. The Harvard Art Museum's connections to the genealogy of Greco-Roman culture set up its theme of History. Everything in the museum is displayed as the continuum of human civilization, from the time of Troy to the recent end of the Colombian civil war.

Additionally, the Harvard Art Museum's atrium is segmented by floor. This is unlike the Gardner Museum's, which has a relatively unbroken line of sight until the glass ceiling. This segmentation is akin to layers of sediment, which accumulate over time and serve as a kind of geological calendar to scientists. The Harvard Art Museum's atrium's segmentation, in kind, acts as an intellectual calendar which spans the ideals of the Greeks and Romans on the first floor to the possibilities of future art in the top floor (which contains study rooms and studios for students).

The similarities between archaeology and the Harvard Art Museum's architecture continues with the presentation of its exhibits. Nearly all of the

8

9

10

exhibits in the museum are entirely encased in glass. This display, coupled with the ancient age of many of the exhibits, reminds of insects trapped in amber, timelessly preserved. Many of the modern sculptures on the third floor, intermingled with classical sculptures, have detritus and debris deliberately attached to them. This gives the false impression of recent excavation.

11

12

The Harvard Art Museum's theme is put front and center by the making its atrium the first room of the building. In this way, the art and the architecture resonate and are able to work together to instill in visitors a greater feeling of meaning than either one alone could accomplish.

Atriums, while being a literal hole in the middle of museums, can tell us a lot about a museum. Just from looking at the atriums, we can determine the overall theme of a museum with sufficient ease and accuracy. Determining this theme allows us to make generalizations about the meaning of the pieces within a museum without diluting the meaning of the individual pieces, balancing a perfect dichotomy of meaning. Once the center of life in a Roman household, atriums continue to be the heart of museums, keeping both their art pieces and their visitors healthy and fulfilled.